Where were we?…

Ah, yes- establishing clarity.

The clarity between the noun arpeggio & the verb arpeggiate.

Not here for last week’s discussion concerning arpeggios?

Then you want to go read this before we continue.

Wow, that was fast.

I didn’t expect you to be back so soon. You’re a quick reader.

Nice.

So I am going to assume that you are totally cool with the concept of what an arpeggio is…

• arpeggio = the notes of a chord played in a scale-like manner

Okay, so onto the next word- arpeggiate. It is the verb version of the word arpeggio and it describes an action that many of you guitar players have undoubtedly already taken at one time or another in your guitar experience. And that is to hold a chord with your left & arpeggiate with your right hand.

And that is done by playing the strings individually or in groups, in any sequence, frequency or duration.

• arpeggiate = to play the notes of a chord individually or in groups, in any sequence, frequency or duration

Now, didn’t I make a point last time to say how I dislike definitions that contain words that need to be defined?…

• sequence = the order of the notes

• frequency = how often a note shows up

• duration = how long each note lasts

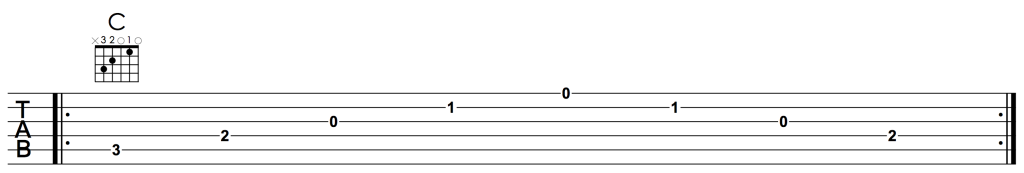

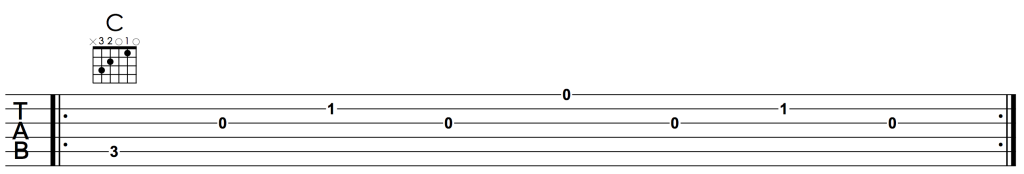

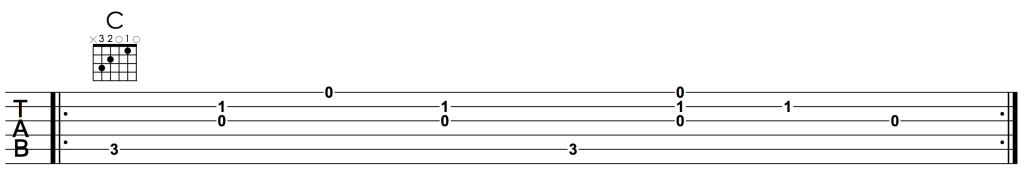

Here are a few examples:

When I said, “playing the strings individually, or in groups… “, I meant that you don’t have to just play one note at a time. Some people misconstrue what arpeggiate entails & that is my ultimate mission here… to clear up any minute details of the scope of the definition of the word.

So the last example shows you said groupage in action.

Right away, I want to emphasize that the most distinct difference between arpeggio & arpeggiating. While both deal with the notes of a chord, the latter involves letting the notes ring over one another, as in, the notes overlap… whereas with an arpeggio, you play the notes from one to the next in a legato fashion.

(You did go back & read Part 1, right?… I mean, don’t just tell me you did if you didn’t because there’s no way you can fake knowing what “legato” means)

Essentially, to arpeggiate is to break the chord up into a series of notes rather than playing all the notes at once, like you do when you strum.

As a matter of fact, there is another name people use for arpeggiate and that is broken chord. This name is used frequently so make sure you know it.

You’ve done so well up to this point, I’d hate to see you derailed by the simple reality that we humans LOVE to have multiple words for the same thing. It makes teaching so much easier. (Has anyone designed a font called “Sarcasm”?… I need it. right. now.)

Notice these examples are repeating patterns. Patterns are a big deal in music. Our brains are wired to look for patterns in things & here’s where you can be creative with coming up with organized approaches to playing the strings individually or in groups, in any sequence, frequency or duration.

In reality, with arpeggiation, anything goes here. So you should take the chords you know & love and experiment with creating your own arpeggiations.

At first, let your inner sense of rhythm take over & play things that sound musical to you. If we discussed the rhythmic possibilities that come along with arpeggiation, we’d be here forever. Just focus on experimenting with various sequences & frequencies of the notes in the chord. Well discuss the details of rhythm & arpeggiation at another time… or future blog.

Maybe you could come up with a one bar pattern & apply it to a four chord progression & play the pattern one time each chord.

Alrighty, I am going to pull the bus over again & point something out here. It’s going to take our little adventure into some interesting places.

(sometimes achieving clarity is like that scary bus route in Bolivia)

Allow me to quote myself (because I am somewhat of an authority on myself).

I said above…

“Essentially to arpeggiate is to break the chord up into a series of notes rather than playing all the notes at once, like you do when you strum.“

The part where I say, “all the notes at once, like you do when you strum”, is interesting. And here’s why…

When you strum a chord, you are not truly playing the notes of the chord all at once. You are in reality, executing a really fast arpeggiation.

Let’s look at the mechanics of strumming…

You are either doing a down strum, which results in hearing the notes in rapid succession from low to high, or you are doing an up strum which results in hearing all the notes in rapid succession from high to low. It just seems to be “all at once” because the notes are going so fast. But it is not truly simultaneous.

And strumming is the most basic of right hand techniques because there isn’t too much finesse involved for the most part, so it is easy for this action to become delegated to the subconscious rather quickly in one’s formative stages of learning to play the guitar…. meaning you probably don’t really think about it too much. The right hand just does it. I’ve found that most players do somewhat realize that strumming is not truly playing the notes simultaneously, but they just haven’t thought about it consciously. You know, those things that you know but maybe don’t know you know until someone asks you about it, and then you go, “Oh yeah, I guess I know that.”

Well, now you know. All this time you’ve been strumming, you’ve really been a “rapid arpeggiator”.

Now I am compelled to tell you that the piano term that is the equivalent of strumming is called rolling, as in “Hey, look at Chopin rolling his chords!”.

Again, it means that you are rapidly “arpeggiating” the notes of the chord in one pitch direction or the other- meaning, up or down. I’ve never heard anyone call strumming rolling on the guitar but, hey, who knows?… maybe you’ll be playing with a piano player some day wondering why when you both play chords.

And perhaps, at this point, your powers of common sense & logic allow you to realize that the opposite of arpeggiating a chord is to play all the notes simultaneously, and that is sometimes referred to as block chords. The true definition of block chords is a little narrower that that , however, most people use it as a way to describe when you play the notes of a chord simultaneously. And the term works for any chordal instrument.

We’re going to finish this subject up in a future blog because, as I suspected, other related concepts & techniques are about to come up as I attempt to address all the aspects of arpeggios & arpeggiating.

As a guitar educator for many decades now, I have seen time & time again that having an incomplete understanding of a particular subject can lead to problems with one’s overall musicianship skills. These missing files on your head’s hard drive tend to create issues in other areas and this can compound itself over time. That’s why articles such as this one are good for filling in the missing information so that you can accurately go from the big picture to the little picture… and back again.

And this subsequently frees you up to create freely on your instrument.

But here’s the deal…

Different people learn in different ways and it behooves you to figure out your own tendencies when you are learning so that you can explore different approaches to mastering a subject. And by “approaches”, I mean checking out different kinds of lessons from different kinds of teachers.

My explanations might not click for you, but for another, they might totally facilitate an epiphany.

I feel a big part of learning is looking at a subject from many different angles.

Now this takes more time, but it is defiantly worth in the long run.

I always start out these articles with the intent to focus on a specific aspect of guitar playing and it almost always branches out into other related topics.

And that’s okay, as long as I drive this bus carefully, we’re gonna arrive at our destination in one piece.

But do we really actually ever arrive?

Find out in Clarity is Underrated – Part 3.

Leave A Response